One week on

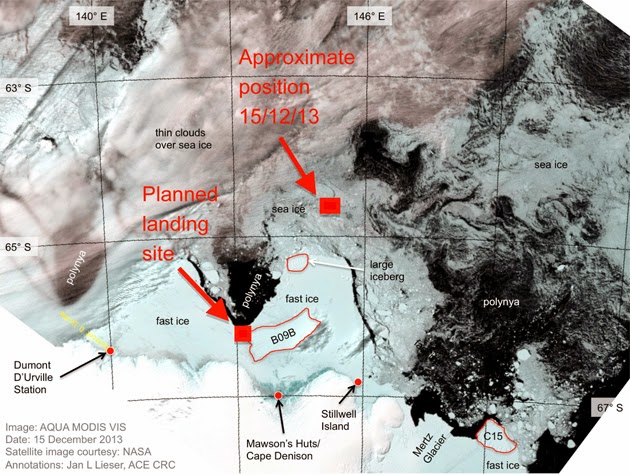

It has been a sobering week. At the time we were initially caught by the sea ice, the Shokalskiy was just 2 to 4 nautical miles from open water. Now the sea ice distance has become even greater with the continued winds from the east, putting our nearest point of exit at some 16 nautical miles. The international effort has been extraordinary and we are incredibly grateful for all the hard work and effort everyone has provided to assist the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 2013-14 in escaping from the ice – a big thanks in particular to the Chinese, French and Australians, co-ordinated by the Australian Maritime Rescue Centre. The winds have eased slightly but at times have reached in excess of 70 kilometres an hour – equivalent to the average conditions experienced by Sir Douglas Mawson’s original expedition a century ago at Cape Denison. It is humbling to consider these men not only survived but thrived, mounting a major scientific expedition. A continent of extremes was ...